The San Antonio Express-News

Jan. 14, 2007

By Robin Ewing

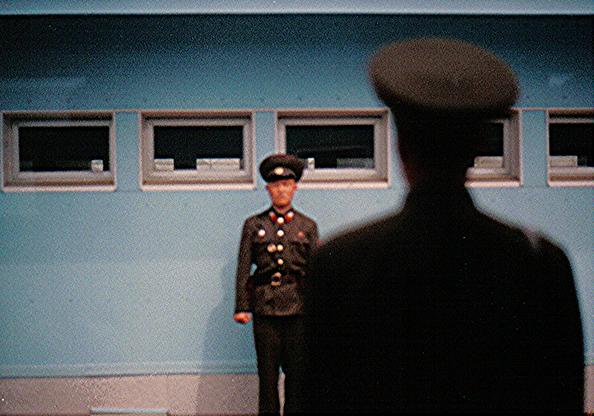

Using the southern end of the rectangular cornflower-blue building as a shield in event of attack, a Republic of Korea solider trains one steady eye on North Korea. The other eye — presumably, as his gold-rimmed aviator sunglasses obscure all eye movement — stares straight at the wall only inches from the tip of his nose. A few yards away, a stony-faced North Korean soldier patrols the northern end of the building. In olive drab, he unflinchingly glares back as he strolls his side of the ankle-high concrete wall, the Military Demarcation Line, which marks the division of the two Koreas. He and his fellow guards have been known to spit over the tiny barrier, make throat-slashing gestures and give the bird. But not this morning. This morning, like most here at the Joint Security Area in the Korean, is a day for tourists.

A bizarre strip of land, the DMZ is 2.5 miles wide, stretches 158 miles coast-to-coast along the 38th parallel and severs the Korean peninsula while restraining one of the largest military forces in the world. The area has been jointly administered by the United Nations Command and North Korea since it was created in 1953 by an armistice agreement calling for a ceasefire to the Korean War. Mostly a no man’s land, this buffer zone supports a diverse ecosystem, separates millions of families and has been the stage for many a violent skirmish. It also draws 150,000 tourists a year to the only spot without fences: the village of Panmunjom, officially called the JSA.

Visiting the JSA is the highlight of all organized tours to the DMZ, the only way to visit the area and the only opportunity most Americans will ever have to step foot in North Korea, a country regularly reported as the last bastion of communism. This is the reason I’ve come, a chance to see the last Cold War frontier. There are a number of tours, and I’ve chosen the United Service Organization’s for two reasons: At $42, it’s the cheapest; and since the DMZ is probably the only war-zone tour in the world led by young American servicemen, I thought the USO was closest to the source.

The buildup to the JSA is surreally like waiting in line for a haunted house; there’s impatient shuffling among the crowd as we await our turn to be scared. The tour began at 7:30 a.m., our full bus departing from the USO’s Camp Kim in downtown Seoul. Twenty-five miles from the outer boundary of the capital, the DMZ is worryingly closer than the city’s international airport. Razor-wire fences interspersed with camouflaged guard posts begin on the city’s fringe; the broad Freedom Highway, wide enough for a barrage of tanks, shoots north following the snaking Imjin River, North Korea distantly visible on the horizon. John, our South Korean tour guide, talks incessantly, smiling and reassuringly asserting our fun through the ending of all sentences with “of course you like.” Standing at the front of the bus, he clutches his microphone tightly, like a child with his favorite Christmas toy, as he smiles and nods at his groggy charges.

By 9 a.m. we’ve arrived at Camp Bonifas, the base camp for the UNC security force, the gunslinger motto “In Front Of Them All” ubiquitously on display. We attend a punctilious 30-minute briefing that heightens the pre-JSA tension. Wholesome, no-nonsense, American male soldiers recount gruesome tales of things gone awry over the years and then instruct us in proper behavior – no motioning or communicating with North Korean guards, no photos unless given permission. We sign a waiver agreeing to no compensation in case of death by enemy action and are checked for proper attire – only recently have “clean jeans” become allowed but no sleeveless shirts, no flip-flops, no tank-tops or anything else considered “provocative” and no athletic attire. The UNC doesn’t want a photo of a sleazy Westerner popping up somewhere as North Korean propaganda. The group clambers into a U.N. bus headed for Panmunjom, a surprisingly small dot – 8,611 square feet, or less than a fifth the size of a football field – near the western end of the DMZ that drops into the dark Yellow Sea.

When I replay my memory of the JSA, it inevitably appears inside a frame, a dreamy grey-blue picture like that in an old ’50s television console. My initial impression was through a camera lens as I marched quietly in single file line across the asphalt road to the U.N. main conference building. No stopping allowed. This was the first opportunity to photograph anything in the DMZ so it was a photo frenzy, obsessive click-click-clicking, everyone intent on preserving the feeling of stumbling upon a Cold-War time capsule. I imagine what we must look like to the North Koreans, a motley assortment of Westerners, cameras fixed to our faces, scuttling by for a minute on the capitalist side of the concrete curb.

Once inside the U.N. main conference room – one of the three long blue buildings which South Korean soldiers stand duty behind in frozen Taekwondo ready positions – I freely step into North Korea. Here, the MDL slices across the room, bisecting the long conference table and represented by a microphone cable. Two doors open into the one-room building, one from the north and one from the south. When visitors from one side are the in the conference room, soldiers (all United Nations guards at the MDL are male, South Korean, taller than average and hold Taekwondo black belts ) block the door leading to the opposite side. The walls are all windows, thick U.N.-blue curtains pulled back allowing mutual gawking between tourists and North Korean soldiers. A surreal zoo-like atmosphere suffuses the room as cameras are pressed against window panes.

With a few exceptions, the DMZ is untainted by human touch, having the unintended result of being the peninsula’s most extraordinary wildlife refuge. For 53 years, animals have roamed and plants have blossomed oblivious to the outside world. According to the DMZ Forum, a non-governmental organization intent on having the DMZ corridor named a UNESCO world heritage site, the DMZ protects 67 percent of Korea’s indigenous flora and fauna, including rare and endangered species, such as the Asiatic black bear, leopard, lynx and hundreds of migratory birds.

Apart from Panmunjon, two odd exceptions to the unspoiled wilderness of the DMZ are the propaganda villages: “Daesung Dong,” or Freedom Village, in the South; and its northern counterpart “Gijong Dong,” called Peace Village in the North and Propaganda Village by the South. The two villages face off over green fields studded with mines.

As our bus lumbered into the DMZ, the lush countryside, a bucolic paradise, unfurled ahead of us. Framed by mountains, rolling green rice fields are tended by bent villagers, pants pushed to the knee as they trudge through calf-deep water. According to John, the South Korean government pays the 226 inhabitants of the farmhouse hamlet of Daesung Dong about $80,000 to $85,000 a year to live there. To qualify for residency, villagers must have lived there before the Korean War or prove relationship to someone who did, spend at least 240 nights a year at home, take care of rice fields within the DMZ and abide by curfew laws. Women can marry into the village but men cannot.

In the North Korean village, tall concrete apartments and government buildings languish emptily, projecting a façade of modernity, though it does sport the world’s tallest flagpole at 52 stories. A makeshift population is reported to be bused in each day, an illusion of prosperity.

Back at Camp Bonifas for an 11 a.m. lunch at the cafateria, the palpable tension I felt melts into a head-shaking feeling of ridiculousness over the two school bullies who patrol the DMZ. The “World’s Most Dangerous Golf Course,” a shabby one-hole course so named by Sports Illustrated because of its proximity to numerous land mines, does little to dissipate the theme-park mood.

But the silliness never fully masks the seriousness. Most of North Korea’s 1.1 million troops are near the border, and during the last 50 years more than 1,000 soldiers have died along the DMZ. In the dark, pub-like Mad Merry Monks gift shop, the former monastery building in Camp Bonifas that sells a plethora of plastic DMZ trinkets, a highly publicized incident is documented in a series of black-and-white photographs: the Axe Murder Incident of 1976, in which an altercation over the trimming of a 40-foot poplar tree resulted in the beating to death of two American officers. Captured in eerie still shots, North Korean soldiers attacked their UNC counterparts with hatchets and metal pikes.

Standing on the breezy hill of the UNC 3rd Outpost, I look down on the site of the ax murders, next to the Bridge of No Return. The green spreads out smoothly here, blending calmly into North Korea, no sign of the barrier that hangs heavy in Korean history. Thousands of prisoners of war were exchanged on this bridge just after the signing of the armistice agreement – if prisoners chose to be repatriated, they could never return. Until a few years ago, massive propaganda signs, gigantic Korean letters, poked through the piney green. South Korea would flash alluring messages promising prosperity for North Korean soldiers, saying things such as “We’ve Sold 10 Million Cars.” The North’s focused on anti-American and anti-Western slogans. But a recent joint resolution put an end to the taunting.

The last stop is the 3rd Tunnel, one of four North Korea has burrowed under the DMZ. The tunnel is more than a mile long and can accommodate 30,000 troops and artillery per hour under the damp arches bored through bedrock. We descend 240 feet in an old mine cart, our bright-yellow hard hats occasionally bumping against the dark rock, bare bulbs dimly pushing back the darkness. The tunnel is pressing, and the idea of a million armed soldiers marching through the darkness is overwhelming. Designed for an attack on Seoul, the tunnel was built in the ’70s under the orders of the former “Great Leader,” Kim Il Sung. The current “Dear Leader,” Kim Jong Il, is a thorn in the side of the international community, but despite the recent testing of a nuclear weapon by North Korea, the DMZ tour is business as usual. In fact, says a UNC media relations officer, DMZ tours have never been cancelled in their 40-year history.

At 3 p.m., the bus wanders back into Seoul, navigating unruly afternoon traffic; pop music detonates in high-pitched melodies from open doorways, women in bright short skirts and gaggles of school children in uniform stride down wide sidewalks, the smells of late lunch drift by in spicy parcels. The Korean frontier suddenly feels years away, lost in the tragic history of war, divided families and faded Cold War memories. Then we glide past the Yongsan military base, where many of the 29,000 U.S. troops stationed in South Korea call home, and the knowledge that this is a country perpetually on the cusp of conflict breaks the city’s petty bustle.