Reviews: A collection of film and TV drama reviews about Asia-Pacific journalists or journalists working in the region with a focus on how the journalist or journalism is portrayed. All reviews are published in the Asia-Pacific Journalism Review.

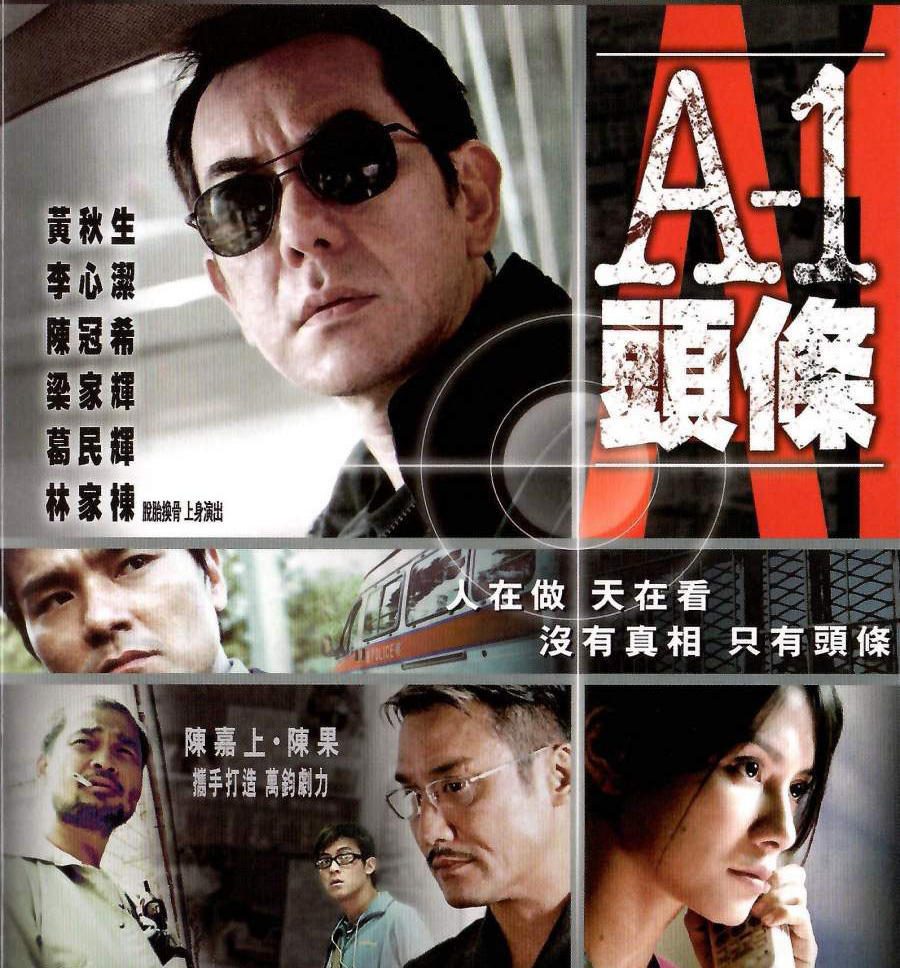

A1 Headline (2004, Hong Kong)

This thriller follows a debt-saddled fashion reporter as she takes a week of unpaid leave from her fictional Hong Kong daily to investigative the suspicious death of her ex-boyfriend and colleague who was working on a mysterious front-page story. She is aided in her listless, haphazard investigation by a motley assortment of helpers, including a dopey photographer with a moped and two debt collectors who start off the film trying to shake her down and end up ferrying her around instead, acting as her muscle and saving her with surprising ease from a burning building.

Despite the dramatic plot all coming together with the dullest of bangs, the bow-tied editor (played by decorated Hong Kong actor Tony Leung Ka-fai sporting Hong Kong’s iconic “egg tart” hairdo) gives a noble speech about the purpose of journalism, invoking the principles of truth, accuracy and the importance of independence from the tycoons that own your paper, which adds some needed backbone to the story. This film is more about what it isn’t than what it is: there is no sensationalism or blood-thirsty press pack; no fight to get the scoop or underhanded tricks to manipulate sources; the scenes aren’t hurried; the bad guys aren’t all that bad. Hong Kong actor Anthony Wong carries the film and it’s worth it just to watch him. Also, like all good journalism films, there is the requisite printing press in action scene.

It’s an entertaining, if not slightly boring, watch: 2.5/5 stars

Balibo (2009, Australia)

Spoiler: All the journalists are murdered in this appalling true story set during the 1975 Indonesian invasion of East Timor.

The film follows a fictionalized version of 53-year-old Australian freelance journalist Roger East as he traverses the island investigating the disappearance of five Australian-TV reporters some three weeks before. (East famously opened a one-man radio bureau in East Timor stringing for ABC Radio and the Australian Associated Press). The narrative shifts between the group of TV journalists, later named the Balibo Five after the town in which they were killed, as they report on Indonesian incursions, their story unfolding in grainy, hand-held footage with a retro filter, and East’s search as he uncovers their murders, getting shot at by helicopters and witnessing the massacre of civilians by Indonesian troops along the way. Two months later, East meets a similar fate.

This is all historical record now. But what really happened to East and the Balibo Five has taken decades to uncover. The film was an attempt to move the Australian government to action after a 2007 coroner’s report indicated the men were deliberately killed. Though the film was banned in Indonesia, a former Indonesian special forces solider, who saw it at a private screening, went on record saying the men were murdered and their bodies burned to cover up news of the invasion. What has also come out since the film is that Australian intelligence had knowledge that the journalists were in danger, did nothing to stop it and then covered it up. (The film has been criticized for leaving out UK, American and Australian involvement in greenlighting and arming the invasion, but it’s clear the filmmakers wanted public outrage aimed in only one direction).

Though much of East’s quest is told with creative license, the overall story is tragically accurate, and the film, which was shot in East Timor, not only brings the murders to light but also touches on the much broader theme of the self-perceived invincibility of western foreign correspondents working in the developing world, highlighted by the fabrication of East’s dying words, “No, I am Australian.” The murders also mark the beginning of a time in which journalists are specifically targeted during conflict.

It’s a hard watch but well worth it. 4/5 stars.

The Journalist (2019, Japan)

A dogged newspaper reporter hits the Tokyo streets to investigate an anonymous fax, something that apparently still happens in Japanese newsrooms, revealing mysterious plans for a shady government-funded school, a topic Japanese audiences are familiar with from the political scandals of the Abe era. Suicides, evil bureaucrats, smear campaigns, a mystery involving a sheep and thoughtful brooding pauses followed by one-word clues written on sticky notes ensue.

Japanese media are facing a crisis of indifference among a growing population of young people who don’t read the news, and this award-winning thriller is a thinly-veiled attempt to make investigative journalism and newspapers sexy again.

The fictional plot is loosely based on a book by real-life Tokyo Shimbun journalist Isoko Mochizuki, a local folk hero for posing challenging questions to government officials and a “problematic” member of the usually compliant press club. (Mochizuki has a few cameos in film. Look out for her at a street demonstration and on a TV talk show that everyone in the film likes to watch.) The movie reporter Erika Yoshioka, clearly based on Mochizuki, looks perpetually both alarmed and confused, but to the script’s credit, maintains her journalistic integrity to get the story. She works with an equally trembly whistleblower from Japan’s intelligence agency, his Orwellian work scenes and long, conflicted stares overlaid with a blue filter for full dystopian effect, as he risks his career and family to do what is right.

At times, the excessive camera shake as journalism gets done is less cinematic and more drunk camera operator, but there is an inspiring montage of a printing press in action, a motif evocative of Hollywood’s Spotlight or The Post. In a country where only 20 per cent of journalist are women, this film, which has been adapted into a TV series by Netflix, has the potential to empower Japan’s aspiring young female journalists.

Overall, despite some flaws, it’s a good watch. 3/5 stars.

The Menu (2016, Hong Kong)

Hong Kong loves a press pack, and a gang of journalists running with cameras to shoot a gory bus crash features early on in this melodramatic spin-off of a 2015 TV series of the same name. The Menu features three of the same TV characters working at a fictional daily, meant to represent one of Hong Kong many free newspapers, battling a rival outlet to cover a hostage situation in a TV studio all set against a backdrop of struggling print media in the internet age. It’s good vs bad journalism here, with reporters invoking outrage as they step right into the storyline’s many ethical pitfalls: from stealing a dead woman’s mobile phone to stumbling into a victim’s stretcher and goading an unstable source. The biggest eye-roll moment, and there are many, comes as an unscrupulous photojournalist frames his shot, hoping to catch just the moment that teetering metal scaffolding falls on a child rather than save her in an obvious and not-quite-right comparison to Kevin Carter’s photo of the starving Sudanese girl and the vulture. There is a significant amount of overacting combined with moments of ridiculousness, but the heavy-handed plot raises real ethical questions about the role reader clicks play in creating a news system designed to reward sensationalism and the lengths to which news outlets will stoop to get the story first.

To be highlighting the death of print media in 2016 feels a bit late, but if you like watching heroic journalists run around the streets of Hong Kong in stylish jackets saying things like “stay hungry” and pretending to be detectives then this is the movie for you. 1.5/5 stars.

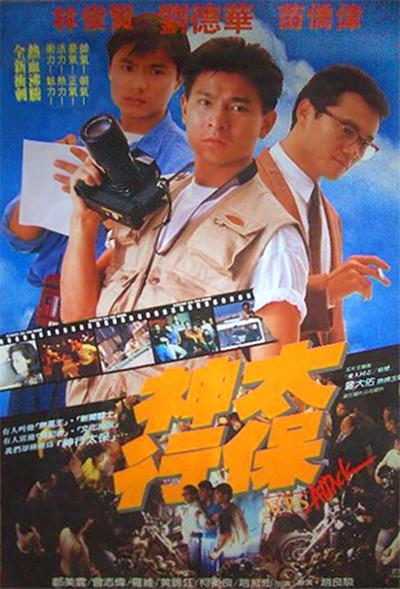

News Attack (1989, Hong Kong)

Heroic newspaper journalists climb buildings to save helpless women and run long distances through the streets of Hong Kong to get to crime scenes or to escape vengeful gangsters for a significant portion of the film all while holding power to account. The male reporters, because only men do things in this movie, liken themselves to soldiers and their cameras to guns in this depiction of a Hong Kong daily in the 1980s. Like so many films about journalism, there is a heavy moral undertone, this time that a newspaper has the power to stop rich men from doing bad things, and there is some charm in the dramatic action scenes, the earnest idealism and shots of a 20th century Hong Kong when editors wore suits, cub reporters are ridiculed for going to journalism school and you could still smoke in the newsroom. 2/5 stars.

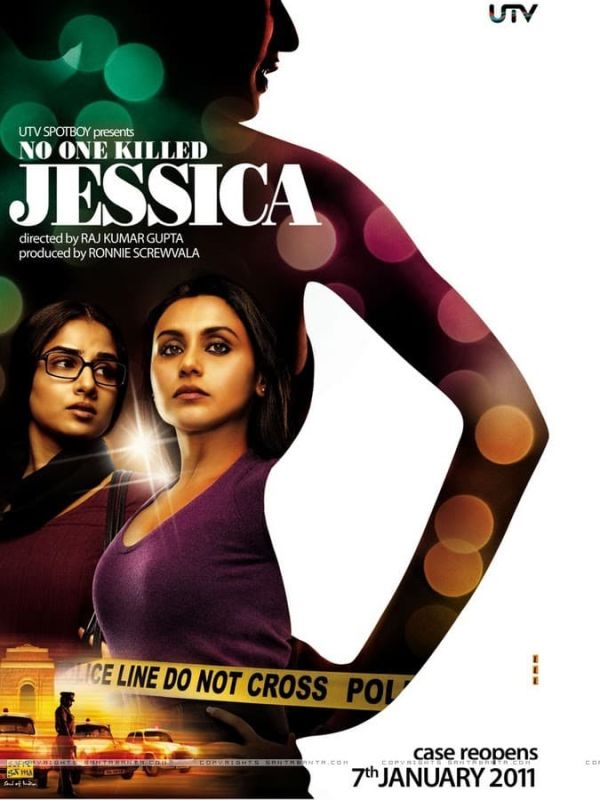

No One Killed Jessica (2011, India)

This Hindi thriller depicts, mostly accurately, the true story of the murder of 34-year-old waitress Jessica Lal in New Delhi in 1999 and the media’s role in bringing about justice for her killing.

Shot and killed at an elite private party after refusing to serve drinks to a group of entitled young men, Jessica becomes a symbol of a corrupt system when 32 witnesses refuse to testify and her murderer is acquitted. This is when the determined TV journalist comes on the scene to get to the bottom of things. In the film, the seven-year battle to get a conviction is led by a fictional TV reporter who appears to be a composite of two real-life NDTV journalists: Barkha Dutt, known for her coverage of the Kargil War, and Sonia Singh, who started an SMS awareness campaign called Justice for Jessica. (In truth, it was news magazine Tehelka that first reported the bribing of witnesses).

Despite an abundance of melodramatic musical montages and a plot that drags in numerous places, the movie is a compelling and insightful look into the power structures of the wealthy and politically connected in India and the role of media activism in harnessing public opinion. Plus, you get to hear determined movie journalists say heart-stirring things like “for the sake of justice and truth.” 3/5 stars

A Taxi Driver (2017, South Korea)

This is a fictionalized version of the true story of German ARD journalist Jürgen Hinzpeter, who, with the help of his local driver, filmed the military massacres of civilians during the Gwangju Uprising in South Korea in 1980, smuggling the footage out of the country in a cookie tin.

The film starts off getting a few things about foreign correspondence wrong: No self-respecting foreign reporter heading into a conflict zone would ever hire a random driver, who doesn’t speak the same language, without a translator or without the driver having any understanding of the risks. It would be unethical to put an unwitting fixer in harm’s way. In truth, the pair had a long-standing relationship, the real Korean driver regularly working with foreign media and briefing visiting reporters on the political situation in fluent English. It’s not the only thing fudged for the sake of drama, but the fictionalized version makes for a comedic and emotional character arc for the driver while truthfully highlighting the important role foreign reporters played in countering government propaganda and bearing witness to the atrocities against Korea’s democratic movement.

For many years, Koreans were banned from talking about the Gwangju uprising, which heralded the years-long transition from authoritarianism to democracy, and it’s clear that this film, with its visual richness and meticulous recreation of the chaos of the massacre, is intended to educate as well as entertain. 3.5/5 stars.

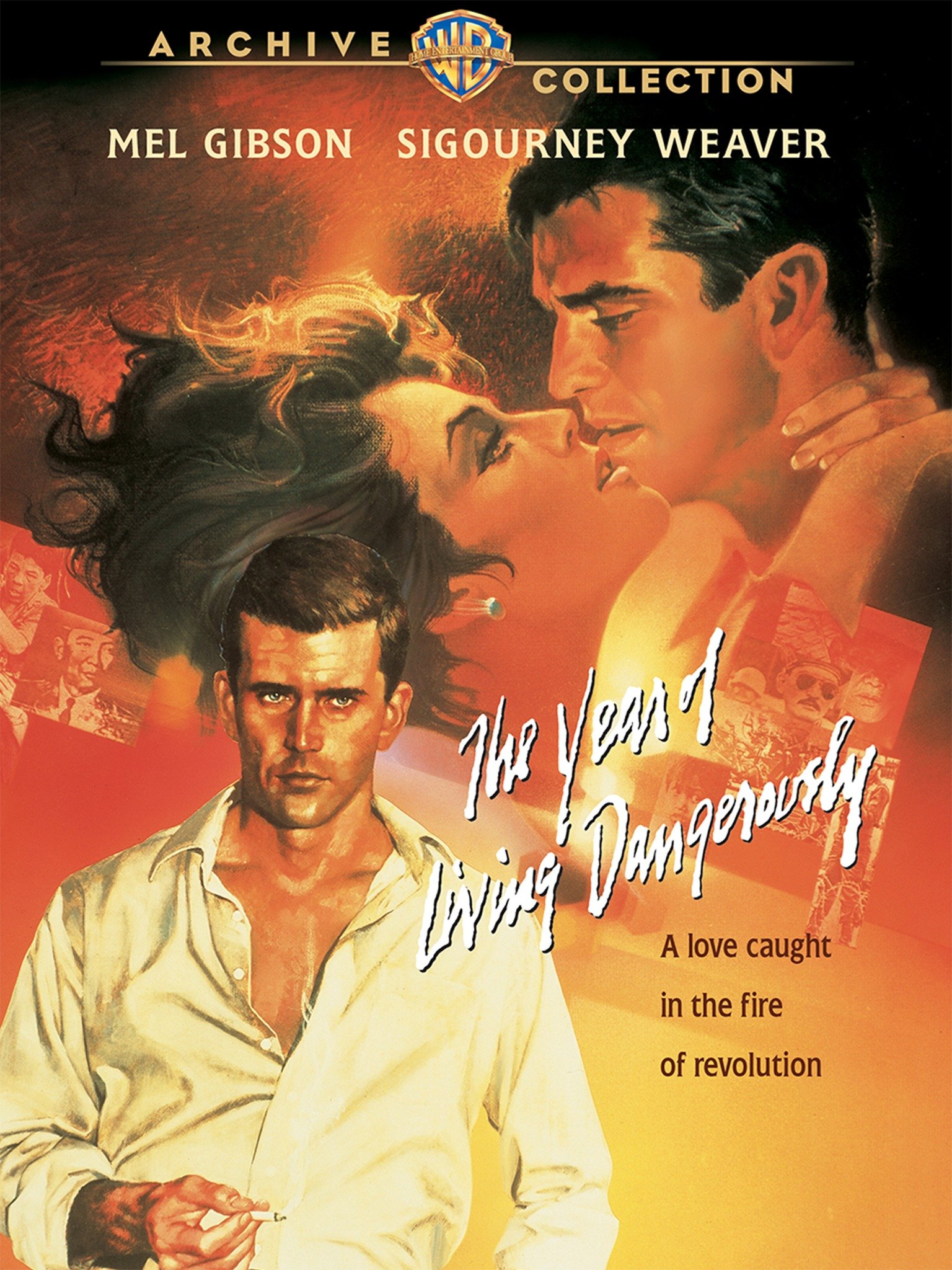

The Year of Living Dangerously (1982, Australia)

Set during the political and social turmoil of 1965 Indonesia, this drama evokes the romantic foreign correspondent of old: white men, shirt sleeves pushed up, drinking in steamy bars, discussing tropical bungalows and sexual conquests, attending embassy parties in tuxedos, stuffing themselves with champagne and oysters and kissing beautiful diplomats in the rain. All of this gets done as the men self-importantly discuss the impending fall of Sukarno, independent Indonesia’s first president, and the rise of communism in Asia against a backdrop of simmering violence, poverty and famine.

The story follows fictional Australian broadcast journalist Guy Hamilton, played by a young pre-fascist Mel Gibson, on his first foreign assignment as he navigates complex relationships with the Jakarta government, his local media assistant, the expatriate community, his love interest (played by Sigourney Weaver) and Indonesia itself all while chasing the biggest story yet, the revolution everyone knows is coming.

It’s an engrossing film that, despite being shot in the Philippines, conjures a time and place long gone. Linda Hunt shines as Billy Kwan, a Chinese-Australian photographer and cameraman, whose poetic narration over the click-clack of the typewriter gives it all a touch of literary noir. The role landed Hunt an Oscar, the first person to ever win the award for portraying the opposite gender, an achievement offset by the filmmakers use of yellowface for her character, a reminder that most of the Asian actors are just backdrop. Kwan plays the role of moral guide and leads Hamilton into the city slums where the human suffering he witnesses there begins to make it into his radio stories, stories, as Kwan puts it, the “journos don’t tell.”

Despite the disappointing decision to use a white actor to play a Eurasian character, the film is a moody and transportive look at foreign correspondence during the last vestiges of colonialism in Indonesia. 4/5 stars.