Episode 01

Real Gone Gals

Real Gone Gals is a program about the women who made, played and changed jazz.

Along the way we’ll listen to a little blues, country and rock-n-roll too. In this episode, I’ll take you on a journey from the brothels of New Orleans to the swinging streets of South Chicago to hear the music made by the women that shaped jazz and blues in the first half of the 20th century.

You’ll hear about Mamie Desdunes, the eight-fingered brothel pianist who taught Jelly Roll Morton his first blues song; Mamie Smith who started the classic blues craze; Ma Rainey, the blues singer who started the first jazz ensembles; and Lovie Austin, one of the greatest jazz blues pianists of her time.

This is the first episode of a series aired on RTHK Radio 3 in Hong Kong in August 2019, written and presented by Robin Ewing and produced by Phil Whelan.

Full Track List for Real Gone Gals

Episode 01 Notes: Photos of New Orleans's Storyville and Chicago's Lovie Austin - Click the + on right to open notes

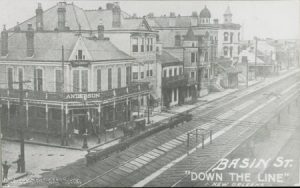

This is a 1908 photo of Basin Street in the red-light district of Storyville, New Orleans, just a few blocks northwest of the French Quarter, then called just “the District” or “Tenderloin” after the better cut of meat the police officers could buy with all their bribes. The street was lined with opulent brothels, called sportin’ houses, named after the madams that owned and ran them. It was in these women-run brothels in Storyville that the greatest collaborations took place for 20 years as musicians experimented with what they called the new “hot” style, what later became known as Dixieland Jazz.

This is a 1908 photo of Basin Street in the red-light district of Storyville, New Orleans, just a few blocks northwest of the French Quarter, then called just “the District” or “Tenderloin” after the better cut of meat the police officers could buy with all their bribes. The street was lined with opulent brothels, called sportin’ houses, named after the madams that owned and ran them. It was in these women-run brothels in Storyville that the greatest collaborations took place for 20 years as musicians experimented with what they called the new “hot” style, what later became known as Dixieland Jazz.

Here is a fantastic resource on Storyville, and a really interesting oral history documentary called “Storyville- The Naked Dance.”

The most notorious and the largest of all the Storyville mansions was Lulu White’s Mahogany Hall. The lavish mansion had five parlours, one of which was completely lined with mirrors, said to have cost $30,000. It was here that many of the women on the piano brothel circuit, including Mamie Desdunes, Rosalind Johnson, Camilla Todd, Edna Mitchell and Wilhelmina Bart de Rouen, would play until dawn. An entire book could be written about the fascinating life of Miss Lulu, as she liked to be called. She was born a slave and became a very shrewd, and very wealthy, business woman who kept files on all her customers that she used when she needed something. At Mahogany Hall, she liked to make a dramatic entrance right at midnight to the song “When the Pale Moon Shines.” She would descend the grand staircase, wearing a red wig and covered in diamonds. Lulu was arrested many times on many different charges, involving sex, guns and liquor. Here are some gorgeous photos of the women of Storyville taken by photographer E. J. Bellocq.

The most notorious and the largest of all the Storyville mansions was Lulu White’s Mahogany Hall. The lavish mansion had five parlours, one of which was completely lined with mirrors, said to have cost $30,000. It was here that many of the women on the piano brothel circuit, including Mamie Desdunes, Rosalind Johnson, Camilla Todd, Edna Mitchell and Wilhelmina Bart de Rouen, would play until dawn. An entire book could be written about the fascinating life of Miss Lulu, as she liked to be called. She was born a slave and became a very shrewd, and very wealthy, business woman who kept files on all her customers that she used when she needed something. At Mahogany Hall, she liked to make a dramatic entrance right at midnight to the song “When the Pale Moon Shines.” She would descend the grand staircase, wearing a red wig and covered in diamonds. Lulu was arrested many times on many different charges, involving sex, guns and liquor. Here are some gorgeous photos of the women of Storyville taken by photographer E. J. Bellocq.

Dolly Douroux Adams started playing Storyville, mostly in Lulu White’s Mahogany Hall, in her uncle Manual “Fess” Manetta’s band when she was only 13. She has been called one the “finest exponents of pure New Orleans, Louisiana-style jazz piano,” and she performed until her death in 1979 in New Orleans.

Dolly Douroux Adams started playing Storyville, mostly in Lulu White’s Mahogany Hall, in her uncle Manual “Fess” Manetta’s band when she was only 13. She has been called one the “finest exponents of pure New Orleans, Louisiana-style jazz piano,” and she performed until her death in 1979 in New Orleans.

Dolly was playing with Punch Miller’s Bunch at Preservation Hall on January 22, 1965. After a lively version of “The Saints Go Marching In,” bass player Papa John Joseph turned to his band mates and said, “That about took everything out of me!” He then collapsed and died on stage, falling on Dolly’s foot.

Listen to a 1962 interview with Dolly here.

New Orleans pianist Jelly Roll Morton was one of the early influencers of New Orleans style jazz. He learned his first ever blues song in 1902 from a woman named Mamie Desdunes, who played piano and sang in dance halls and brothels of New Orleans. She was missing two fingers on her right hand. Mamie taught him the gorgeous blues song that Jelly Roll played for Alan Lomax in 1938 that he calls “Mamie’s Blues”. There are no recordings of Mamie because she died young in 1911, nine years before the the first blues album by an African-American and six years before the first jazz albums were recorded.

New Orleans pianist Jelly Roll Morton was one of the early influencers of New Orleans style jazz. He learned his first ever blues song in 1902 from a woman named Mamie Desdunes, who played piano and sang in dance halls and brothels of New Orleans. She was missing two fingers on her right hand. Mamie taught him the gorgeous blues song that Jelly Roll played for Alan Lomax in 1938 that he calls “Mamie’s Blues”. There are no recordings of Mamie because she died young in 1911, nine years before the the first blues album by an African-American and six years before the first jazz albums were recorded.

Here’s a great resource on Mamie Desdunes.

It was the classic blues craze that swept across America in the 20s that gave rise to the big band jazz sound so popular in the 30s and 40s. 1920 was the year Mamie Smith and her Jazz Hounds recorded the song “Crazy Blues” for Okeh records. It was a sensational hit, selling more than 100,000 copies in the first month and more than 1 million in 6 months and started what the record companies called “race records”. Trombonist Clyde Berhnart said “Crazy Blues” was the only song you could hear in the streets, all at different speeds on the wind-up Victrola record player.

It was the classic blues craze that swept across America in the 20s that gave rise to the big band jazz sound so popular in the 30s and 40s. 1920 was the year Mamie Smith and her Jazz Hounds recorded the song “Crazy Blues” for Okeh records. It was a sensational hit, selling more than 100,000 copies in the first month and more than 1 million in 6 months and started what the record companies called “race records”. Trombonist Clyde Berhnart said “Crazy Blues” was the only song you could hear in the streets, all at different speeds on the wind-up Victrola record player.

Here’s a video of Mamie singing a version of “Crazy Blues” in 1935.

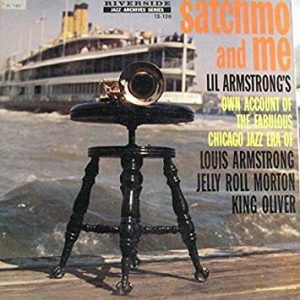

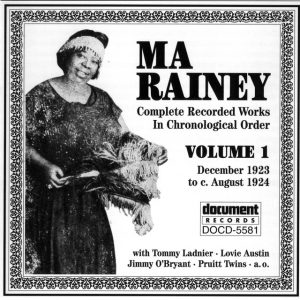

Ma Rainey, one of the greatest blues singer in history and nicknamed the “Godmother of the Blues,” was responsible for growing the classic blues band from the basic setup of guitar or piano to the full instrumental jazz ensemble. Ma Rainey helped create that big band sound that dominated jazz through the 1940s. Ma Rainey recorded 100 songs between 1923 and 1928 on Paramount Records. This is an album cover that lists Lovie Austin, a pianist who led the house band for Paramount and played with nearly every blues singer that recorded with the company.

Ma Rainey, one of the greatest blues singer in history and nicknamed the “Godmother of the Blues,” was responsible for growing the classic blues band from the basic setup of guitar or piano to the full instrumental jazz ensemble. Ma Rainey helped create that big band sound that dominated jazz through the 1940s. Ma Rainey recorded 100 songs between 1923 and 1928 on Paramount Records. This is an album cover that lists Lovie Austin, a pianist who led the house band for Paramount and played with nearly every blues singer that recorded with the company.

Here’s a great collection of songs that Ma Rainey and Lovie Austin recorded together.

Ma was wild, and her exploits were known far and wide. She was arrested in Chicago in 1925 for running an indecent party after police, responding to a noise complaint, caught Ma and several young women in an orgy. Bessie Smith had to bail her out of jail.

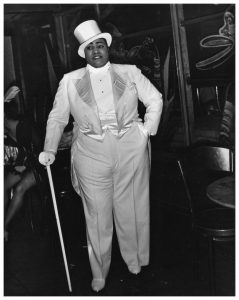

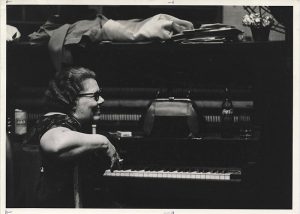

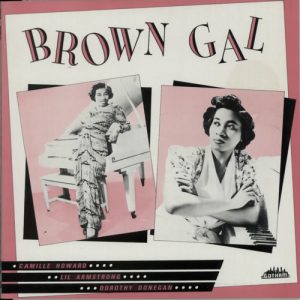

Lovie Austin was known for racing around Chicago in a Stutz Bearcat with leopard skin upholstery, similar to the photo below of a 1920’s Bearcat. She was always dressed to the nines on her way to her job as the musical director and pit pianist of the Monogram Theatre. The theatre was a dump, but all the big acts played here. Lovie was from Tennessee, next door neighbour and childhood friend with blues singer Bessie Smith, and she studied music in college, a fairly big deal for this time. Lovie is considered, along with Lil Hardin Armstrong (whom you’ll hear about in detail in the next episode), the greatest jazz blues pianist of her time.

Lovie Austin was known for racing around Chicago in a Stutz Bearcat with leopard skin upholstery, similar to the photo below of a 1920’s Bearcat. She was always dressed to the nines on her way to her job as the musical director and pit pianist of the Monogram Theatre. The theatre was a dump, but all the big acts played here. Lovie was from Tennessee, next door neighbour and childhood friend with blues singer Bessie Smith, and she studied music in college, a fairly big deal for this time. Lovie is considered, along with Lil Hardin Armstrong (whom you’ll hear about in detail in the next episode), the greatest jazz blues pianist of her time.

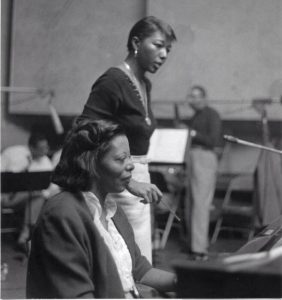

In 1922, Lovie helped influential blues singer Alberta Hunter write down and copyright a song that Alberta had composed in her head. Then they recorded it together. It was called “Down Hearted Blues,” and when Bessie Smith sang it in 1923, it made her a star. Fast forward almost 40 years and Lovie and Alberta met in a Chicago studio in 1961 to play the song together again for the first time since they wrote it. In their recording, Lovie uses her signature two-handed approach. With her left hand she maintains a steady rocking bass note and with her right she improvises counter melodies.

In 1922, Lovie helped influential blues singer Alberta Hunter write down and copyright a song that Alberta had composed in her head. Then they recorded it together. It was called “Down Hearted Blues,” and when Bessie Smith sang it in 1923, it made her a star. Fast forward almost 40 years and Lovie and Alberta met in a Chicago studio in 1961 to play the song together again for the first time since they wrote it. In their recording, Lovie uses her signature two-handed approach. With her left hand she maintains a steady rocking bass note and with her right she improvises counter melodies.

There is no video footage of Lovie playing, but here’s a great video of Alberta singing “Downhearted Blues” in 1982.

Jazz pianist genius Mary Lou Williams recalled seeing Lovie on a trip to Pittsburgh around 1920 when she was kid. She said, “I remember seeing this great woman sitting in the pit and conducting a group of five or six men, her legs crossed, a cigarette in her mouth, playing the show with her left hand and writing music with her right. Wow!…My entire concept was based on the few times I was around Lovie Austin. She was a fabulous woman and a fabulous musician too. I don’t believe there’s a woman around now who could compete with her. She was a greater talent than many of the men of this period.”

Jazz pianist genius Mary Lou Williams recalled seeing Lovie on a trip to Pittsburgh around 1920 when she was kid. She said, “I remember seeing this great woman sitting in the pit and conducting a group of five or six men, her legs crossed, a cigarette in her mouth, playing the show with her left hand and writing music with her right. Wow!…My entire concept was based on the few times I was around Lovie Austin. She was a fabulous woman and a fabulous musician too. I don’t believe there’s a woman around now who could compete with her. She was a greater talent than many of the men of this period.”

Episode 02

Real Gone Gals

In this episode, we’ll go to 1920s Chicago with its rowdy, blues-based jazz and nightclubs full of drunken brawls, shootings and stabbings to learn about one of the most influential jazz piano players in history: Lil Hardin Armstrong. Next, we’ll check out the cultural explosion in 1930’s Harlem and listen to the music of the woman most emblematic of the elegance, glamour and sophistication of New York City’s jazz scene: Hazel Scott.

This is the second episode of a series aired on RTHK Radio 3 in Hong Kong in August 2019, written and presented by Robin Ewing and produced by Phil Whelan.

Episode 02 Notes: Photos and Videos of Chicago's Lil Hardin & New York's Hazel Scott - Click the + on right to open notes

In 1917, when Lillian “Lil” Hardin was 19, she and her mother moved up to Chicago from their hometown in Memphis, Tennessee. Lil and her mother were part of the Great Migration, the movement of more than 1.6 million African Americans from the South to the urban North during this time.

In 1917, when Lillian “Lil” Hardin was 19, she and her mother moved up to Chicago from their hometown in Memphis, Tennessee. Lil and her mother were part of the Great Migration, the movement of more than 1.6 million African Americans from the South to the urban North during this time.

After an audition in a Chinese restaurant, Lil got her first gig playing with Lawrence Duhe and his New Orleans Creole Jazz band, the hottest band in town. King Oliver soon took over and Lil was the star. Everyone came to see the “Hot Miss Lil” pound out the beat on the piano. When her strict mother found out, she only allowed Lil to keep the job if she could come pick her up when the show finished at 1am. Lil did much of the composing and arranging, making her one of the biggest influences on the development of jazz from its simple Dixieland roots to the more complex swing of the 20s and 30s.

Before the recording industry got big, musicians hung out in sheet music stores. Pianos were expensive, so for many musicians, their only access to a piano was in one of these stores. They went there to play, learn new songs and socialize.

Before the recording industry got big, musicians hung out in sheet music stores. Pianos were expensive, so for many musicians, their only access to a piano was in one of these stores. They went there to play, learn new songs and socialize.

The stores hired “demonstrators,” piano players to lure people inside by playing the latest tunes. Lil got a job as a demonstrator in a sheet music store on South State Street for $3 a week. Lil became the store’s star attraction. She was 19 years old, but she was so small, everyone thought she was 10. They called her the jazz wonder child.

It was in the Jones Music Store that she met New Orleans’s pianist Jelly Roll Morton and her playing style was forever changed. Lil said, “In no time at all, he had the piano rockin,’ and he played so heavy, and ooh, goosepimples were sticking out all over me. I said oh gee, what a piano player… After that, I played just as hard as I could, just like Jelly Roll did, and till this day I am still a heavy piano player.”

Lil was a tiny woman, only about 39 kg/85 pounds but she could play her piano with incredible force. It was quite the sight to see Lil in her flapper dress, pearls and high heels pounding away on the piano with her signature ferocity, her slender arms pumping and her feet stomping.

Lil recorded an oral history album called “Satchmo and Me” in 1957 where she talks about her job in the sheet music store, meeting Jelly Roll and her first gig with the Creole Jazz Band. Listen to some clips from the album here.

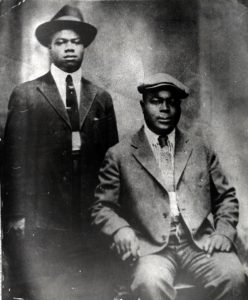

Joe King Oliver (right) convinced his old friend and trumpeter Louis Armstrong ( left) to leave New Orleans to come play in his band. When 24-year-old Lil first met the 21-year-old Louis she said, “I was very disappointed – I didn’t like anything about him. I didn’t like the way he was dressed. I didn’t like the way he talked. I just didn’t like him. I was very disgusted.” He was a short, fat country boy and she was an elegant, educated, city girl. But Louis was smitten with Lil and pretty soon, despite her disgust, they fell in love.

Joe King Oliver (right) convinced his old friend and trumpeter Louis Armstrong ( left) to leave New Orleans to come play in his band. When 24-year-old Lil first met the 21-year-old Louis she said, “I was very disappointed – I didn’t like anything about him. I didn’t like the way he was dressed. I didn’t like the way he talked. I just didn’t like him. I was very disgusted.” He was a short, fat country boy and she was an elegant, educated, city girl. But Louis was smitten with Lil and pretty soon, despite her disgust, they fell in love.

Two years later in 1924, they got married, becoming jazz’s first power couple.

Lil and Louis were inseparable, and she had a huge impact on him. She got him to dress better, lose weight, have more fun, sing and be more confident. She convinced him to leave King Oliver’s band, where he was only ever going to be second trumpet, and go out on his own.

Lil and Louis were inseparable, and she had a huge impact on him. She got him to dress better, lose weight, have more fun, sing and be more confident. She convinced him to leave King Oliver’s band, where he was only ever going to be second trumpet, and go out on his own.

She arranged recording sessions for him, wrote songs for him, got him jobs, helped him open his own club and designed and sewed his suits, even after he started having multiple affairs and moved in with another woman. Louis Armstrong might have been a musical genius, but he owes his success to Lil.

When it was good, it was good, and Lil and Louis had a lot of fun in 1920s Chicago. They loved to get dressed up and go on church picnics, which usually ended up with everyone drunk and fighting. They bought and furnished an apartment for Louis’s mother. They spent quiet evenings at home with Lil playing the classics on a beautiful Kimball piano.

Lil and Louis’s prohibition-era Chicago was a wild, and dangerous, place to be. The gangsters ruled, and Al Capone, pictured here, was the biggest and most infamous of them all. When he became the boss in 1925, he grew his empire of gambling, prostitution and bootlegging through violence and fear. The Tommy submachine gun was the weapon of choice and the people of South Chicago lived in terror.

Lil and Louis’s prohibition-era Chicago was a wild, and dangerous, place to be. The gangsters ruled, and Al Capone, pictured here, was the biggest and most infamous of them all. When he became the boss in 1925, he grew his empire of gambling, prostitution and bootlegging through violence and fear. The Tommy submachine gun was the weapon of choice and the people of South Chicago lived in terror.

But Al Capone loved music and he was a frequent patron of the jazz clubs on State Street, where he tipped well as long as the musicians played when and where he told them to. Louis called him that “cute little fat boy.” The clubs Capone supplied illegal liquor to were some of the safest in the neighbourhood.

Lil is the one who created the studio band Louis Armstrong and his Hot Five, pictured here, which made some of the best selling jazz records in the country. She wrote and arranged many of the songs, including what is considered her masterpiece, Struttin’ with some Barbecue.

Lil is the one who created the studio band Louis Armstrong and his Hot Five, pictured here, which made some of the best selling jazz records in the country. She wrote and arranged many of the songs, including what is considered her masterpiece, Struttin’ with some Barbecue.

The Hot Five made their last recording in 1927, and by 1931, Lil and Louis were broken up for good, even though at one point Lil sued Louis over a copyright and refused to give him a divorce until 1938.But Lil never got over Louis, and she never stopped wearing her wedding ring, even after he remarried. Much of the music Lil wrote and sang in the 30s is about the pain of losing Louis, such as one of her most famous songs “Just for a Thrill,” which was covered by Ray Charles in the 1950s.

After the breakup, Lil strikes out on her own. She joins an all-women band with Alma Scott (Hazel’s mother), becomes a band leader, forms her own band, records with a number of artists, performs and puts out her own albums. At one point, she opens a restaurant called Swing Shack and becomes a teacher. In the 1950s, she tours Europe, and in 1961, she records her last album in Chicago.

After the breakup, Lil strikes out on her own. She joins an all-women band with Alma Scott (Hazel’s mother), becomes a band leader, forms her own band, records with a number of artists, performs and puts out her own albums. At one point, she opens a restaurant called Swing Shack and becomes a teacher. In the 1950s, she tours Europe, and in 1961, she records her last album in Chicago.

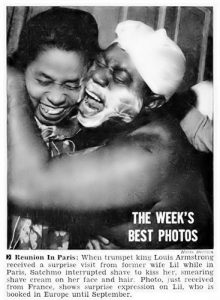

In the second photo, Lil makes a surprise visit to see Louis in Paris, where they are both touring separately. This was long after they were divorced but they still had a connection.

In the second photo, Lil makes a surprise visit to see Louis in Paris, where they are both touring separately. This was long after they were divorced but they still had a connection.

On Aug 27, 1971 Lil is asked to play in a memorial concert for Louis Armstrong at the Civic Center Plaza in Chicago. He had died just seven weeks before, and 2,000 people came out for the outdoor lunchtime concert. Lil, who was 73, was wearing a brightly coloured print dress and silver slippers. She was introduced and sat down at the piano to play W.C. Handy’s St Louis Blues. The crowd cheered. Lil was grinning, her eyes sparkling, full of energy. As usual, her piano was loud and forceful. She played the last note of the song, held it, and just as it ended, she fell to the floor. Lil Hardin Armstrong died right there on stage of a heart attack.

This is the only video footage available of Lil playing. It’s a kinescope from “Chicago, and All That Jazz,” a 1961 Dupont Show of the Week on NBC. Lil, 63 here, is on piano and jazz singer and comedian Mae Barnes is on the snare drum. In the second half, they sing Heebie Jeebies, a song Louis made famous when he dropped the lyrics during a recording session and scatted instead.

This is the only video footage available of Lil playing. It’s a kinescope from “Chicago, and All That Jazz,” a 1961 Dupont Show of the Week on NBC. Lil, 63 here, is on piano and jazz singer and comedian Mae Barnes is on the snare drum. In the second half, they sing Heebie Jeebies, a song Louis made famous when he dropped the lyrics during a recording session and scatted instead.

By the 1930s, New York is the cultural capital of the United States and the Harlem Renaissance is in full swing. Every night across the neighborhood, musicians, dancers, comedians and writers perform for packed houses. Some notable Harlem entertainers include cross-dressing singer and pianist Gladys Bentley (left on desktop, bottom on mobile), who was backed by a chorus line of drag queens; jazz singer and entertainer Adelaide Hall (middle left) led the highest grossing show ever at the Cotton Club called the Cotton Club Parade that caused a sensation with the use of nitrogen smoke for the first time; Blanche Calloway (middle right) often led her all-male band, the Joy Boys, at the Apollo or the Harlem Opera House; singer and actress Ethel Waters (right), who sang at the Plantation Club when she wasn’t on Broadway.

It is in Harlem that 5-year-old Hazel Scott (pictured here at 3 or 4) and her mother made their home when they stepped off the boat from their native Trinidad in the Caribbean. A child prodigy, 3 year old Hazel shocked her grandmother by playing a lullaby by ear with both hands on the piano.

It is in Harlem that 5-year-old Hazel Scott (pictured here at 3 or 4) and her mother made their home when they stepped off the boat from their native Trinidad in the Caribbean. A child prodigy, 3 year old Hazel shocked her grandmother by playing a lullaby by ear with both hands on the piano.

Hazel auditioned for Juilliard, the country’s most prestigious music conservatory, when she was 8. During her audition, she played Rachmaninov’s “Prelude in C Sharp Minor” but her little hands couldn’t span enough of the keys to reach the minor chords, so she improvised,. Juilliard’s terrifying founder heard the improvisation from the hallway and stormed into the audition room to confront the blasphemer who would dare paraphrase Rachmaninov. When he saw little Hazel he was shocked. The auditions director whispered to him, “I am in the presence of a genius.” Scott was admitted to Juilliard.

On Oct 24, 1929, the stock market crashed and the 1930s opened with the Great Depression, which lasted nearly 10 years. Just like everyone in Harlem, Hazel, her mother Alma and her grandmother Margaret were hit hard by the depression. Breadlines were common place and women congregated under elevated train tracks hoping for daywork cooking and cleaning. The ever resourceful Alma Scott decided the money was in music, so she taught herself the saxophone. Alma was so good, she gets a gig with the wildly successful trumpeter Valaida Snow (whom you’ll hear about in the next episode). After Valaida, Alma joined Lil Hardin’s band and then Chick Webb’s and then eventually formed her own. The Scott house became a hangout for musicians who all mentored young Hazel. She called the pianist Fats Waller “uncle” and the great piano virtuoso Art Tatum “Papa Daddy.” She considered Billie Holiday her older sister. Billie’s biggest advice to Hazel? “Never let them see you cry.”

This is a photo of Billie Holiday singing at Café Society. The club opened in 1938 as the only truly integrated club in New York City. It also leaned politically left, with connections to the Communist Party, and billed itself as “the wrong place for the right people”. On opening night, jazz legend Billie Holiday premiered the controversial song “Strange Fruit,” a brutal and haunting song about a lynching and one of the first protest songs of the Civil Rights movement. She later goes on to stun Café Society audiences by singing it at the close of every night, the light dimmed, only a spot light on her face. Here’s a video of Billie singing the song in 1959.

This is a photo of Billie Holiday singing at Café Society. The club opened in 1938 as the only truly integrated club in New York City. It also leaned politically left, with connections to the Communist Party, and billed itself as “the wrong place for the right people”. On opening night, jazz legend Billie Holiday premiered the controversial song “Strange Fruit,” a brutal and haunting song about a lynching and one of the first protest songs of the Civil Rights movement. She later goes on to stun Café Society audiences by singing it at the close of every night, the light dimmed, only a spot light on her face. Here’s a video of Billie singing the song in 1959.

Billie insisted that Cafe Society book the mostly unknown Hazel Scott. When 19-year-old Hazel made her way onstage, she was stunningly beautiful, in a floor-length, fitted white satin strapless gown that made her look nude when she sat behind the piano. She had gardenias in her hair and she sparkled with diamonds. She started to expertly play the classics — Bach, Liszt, Rachmaninov –and then, for each song, about a minute in, in it what was to become her signature move, she looked at the audience, flashed them a sultry, mischievous smile and in mid-measure, sped it all up, adding syncopation and swing and a little Harlem Stride to her improvisations. Watch Hazel swing the classics here.

Billie insisted that Cafe Society book the mostly unknown Hazel Scott. When 19-year-old Hazel made her way onstage, she was stunningly beautiful, in a floor-length, fitted white satin strapless gown that made her look nude when she sat behind the piano. She had gardenias in her hair and she sparkled with diamonds. She started to expertly play the classics — Bach, Liszt, Rachmaninov –and then, for each song, about a minute in, in it what was to become her signature move, she looked at the audience, flashed them a sultry, mischievous smile and in mid-measure, sped it all up, adding syncopation and swing and a little Harlem Stride to her improvisations. Watch Hazel swing the classics here.

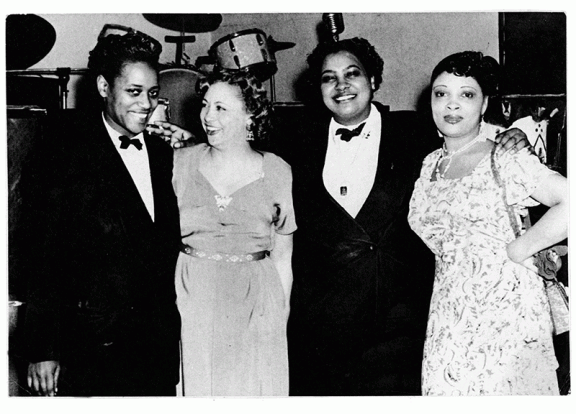

Hazel quickly became Café Society’s biggest star. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt stopped in one night to hear her play, and they had dinner. Hazel met Frank Sinatra and the two became close friends for a while. This is also where she met her future husband, the man who became the first black congressman from New York, Adam Clayton Powell Jr (pictured middle). The two will go on to have a tumultuous and sensational 15 year marriage with an extravagant lifestyle closely tracked and photographed by the press.

Hazel quickly became Café Society’s biggest star. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt stopped in one night to hear her play, and they had dinner. Hazel met Frank Sinatra and the two became close friends for a while. This is also where she met her future husband, the man who became the first black congressman from New York, Adam Clayton Powell Jr (pictured middle). The two will go on to have a tumultuous and sensational 15 year marriage with an extravagant lifestyle closely tracked and photographed by the press.

Hazel was one of the highest-paid black artists of her era, and she and her husband had no trouble spending her money. They traveled by chauffeured limousine and were photographed horseback riding, boating and going to clubs. Hazel had her hands insured by Lloyds of London, owned one of the largest fur collections of anyone in show business and wore a $12,000 necklace.

Hazel went to Hollywood. She loved piano tricks, such as having her hands race towards each other on the keyboard and then cross, video here. She also liked to show off by playing two concert grand pianos at once, a hand on each keyboard, amazing video here. At the 2019 Grammys, Alicia Keys imitated this two-piano trick and even shouted out the name Hazel Scott.

Hazel went to Hollywood. She loved piano tricks, such as having her hands race towards each other on the keyboard and then cross, video here. She also liked to show off by playing two concert grand pianos at once, a hand on each keyboard, amazing video here. At the 2019 Grammys, Alicia Keys imitated this two-piano trick and even shouted out the name Hazel Scott.

She also regularly fought against segregation and discrimination. In one of her Hollywood movies, she staged a strike because she found the dirty aprons the black actress had to wear degrading. She won the battle, the women appeared in the scene is clean floral dresses, but she was ostracized from Hollywood for more than a decade. Here’s a video of the movie scene.

In 1950, Hazel got her own weekly TV show, The Hazel Scott Show. It was so successful it went national and she played three times a week, making her the first black person to ever host a national show.

In 1950, Hazel got her own weekly TV show, The Hazel Scott Show. It was so successful it went national and she played three times a week, making her the first black person to ever host a national show.

But later that year in 1950, Hazel went before Joseph McCarthy’s Committee on Un-American Activities to defend accusations that she was a communist from her days at Café Society. She told the committee members, “Mudslinging and unverified charges are just the wrong ways to handle this problem ,” and “We should not be written off by the vicious slanders of little and petty men.” Though her name was cleared, her show was cancelled and she couldn’t get a concert booking. She left for Europe, where she lived for the next decade.

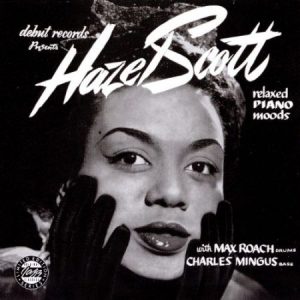

Despite her blacklisting in the US, Hazel went on to have a long career, in 1955 recording Relaxed Piano Moods with Charlie Mingus on bass and Max Roach on drums, considered one of the best jazz trios ever assembled and some of her greatest work. Here is a video of her playing and singing Foggy Day with Mingus and Roach.

Despite her blacklisting in the US, Hazel went on to have a long career, in 1955 recording Relaxed Piano Moods with Charlie Mingus on bass and Max Roach on drums, considered one of the best jazz trios ever assembled and some of her greatest work. Here is a video of her playing and singing Foggy Day with Mingus and Roach.

In 1981, at the age of 61, Hazel diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. As she lay in her hospital bed, her friend Dizzy Gillespie, stood at her side, put a mute in his trumpet and softly played one of her favourite songs, “Alone Together.” Hazel revived briefly, smiled and then died, surrounded by music, friends and family.

Episode 03

Real Gone Gals

Real Gone Gals is a program about the women who made, played and changed jazz.

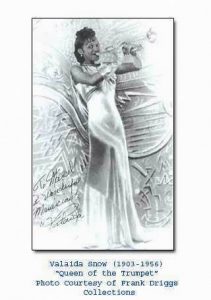

From 1920s Shanghai to 1940s Los Angeles, in this episode we’ll meet the “Queen of the Trumpet,” the women who liked to call herself “Little Louis” and tell everyone she was the second best trumpeter in the world, a hardworking, powerhouse of a musician who also managed to cause a scandal or two, the talented, the beautiful and the highly entertaining, Valaida Snow. We’ll hear one of only two trumpet recordings from Dolly Jones in the 1920s and then listen to the trombone of one of the most genius musical arrangers in jazz, Melba Liston. Finally, we’ll end with the smooth bebop of Vi Redd on tenor sax.

This is the third episode of a series aired on RTHK Radio 3 in Hong Kong in August 2019, written and presented by Robin Ewing and produced by Phil Whelan.

Episode 03 Notes: Photos and Videos of the jazz horns: Valaida Snow, Dolly Jones, Melba Liston & Vi Redd - Click the + on right to open notes

– One of the greatest entertainers in the business, Valaida Snow was known as the “Queen of the Trumpet,” but she liked to tell everyone her nickname was “Little Louis.” This made her, as she said, the second best trumpeter in the world. In truth, she was not only a talented powerhouse of a musician who learned to play 10 instruments as a child vaudeville performer and worked harder than anyone, but she was also a theatrical personality who told more than a few tall tales and caused a scandal or two in her travels around the world.

One of the greatest entertainers in the business, Valaida Snow was known as the “Queen of the Trumpet,” but she liked to tell everyone her nickname was “Little Louis.” This made her, as she said, the second best trumpeter in the world. In truth, she was not only a talented powerhouse of a musician who learned to play 10 instruments as a child vaudeville performer and worked harder than anyone, but she was also a theatrical personality who told more than a few tall tales and caused a scandal or two in her travels around the world.

Valaida was born in industrial Chattanooga, Tennessee in 1904. After a marriage at 15 that is over as fast as it begins, a teenage Valaida sets out on her own, working as a singer, dancer and trumpeter in musical shows and in theaters all over the US. She eventually lands in Chicago and gets a gig working with Louis Armstrong at the Sunset Cafe on the Stroll.

In 1926, on stage at the Sunset Cafe, Valaida lines up seven pairs of shoes — ballet shoes, adagio shoes, tap shoes, Turkish slippers, Chinese straw sandals, Dutch clogs, and Russian boots- and does a different dance in each one. For the tap number, “she tapped just like Bojangles,” pianist Earl Hines says. When Louis Armstrong sees her show, he is thrilled. “Boy, I never saw anything that great,” he says.

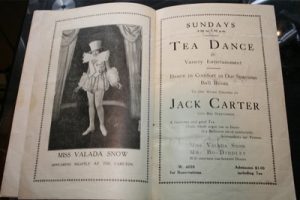

That same year, Valaida leaves for Shanghai. In the 1920s, Shanghai is one of the most cosmopolitan cities in the world, the Paris of the East, and the locals are enthralled with that new American jazz sound. Valaida gets a spot with Jack Carter’s Serenaders at the Plaza Hotel just off the Bund.

That same year, Valaida leaves for Shanghai. In the 1920s, Shanghai is one of the most cosmopolitan cities in the world, the Paris of the East, and the locals are enthralled with that new American jazz sound. Valaida gets a spot with Jack Carter’s Serenaders at the Plaza Hotel just off the Bund.

Twenty-four year old Valaida is the star of the show, playing trumpet, singing and dancing. She does all kinds of tricks with her instrument and improvises tremendous solos. She tap dances and finishes her act sliding on her knees through the audience. Her favorite number was said to be “My Blue Heaven.”

The Plaza immediately puts out an ad offering US$1,000 to anyone who can produce a show to match Valaida, “America’s most versatile stage celebrity.” The photo here is an ad for the same show at the Carlton Cafe in Shanghai in 1928.

Valaida spends more than two years in Shanghai and then tours Asia, including performances in Manila, Indonesia, Thailand, Burma, Sri Lanka, India and Singapore. She even spends a week at the Star Theatre, just behind the Peninsula Hotel in Tsim Sha Tsui in Hong Kong. In Jakarta, their Indonesian guitarist describes how they pack the house. “Almost all their numbers were played like fireworks,” he says.

Valaida spends more than two years in Shanghai and then tours Asia, including performances in Manila, Indonesia, Thailand, Burma, Sri Lanka, India and Singapore. She even spends a week at the Star Theatre, just behind the Peninsula Hotel in Tsim Sha Tsui in Hong Kong. In Jakarta, their Indonesian guitarist describes how they pack the house. “Almost all their numbers were played like fireworks,” he says.

At the end of her Asia tour, Valaida isn’t ready to return home, so she heads to Egypt and then into Europe, playing for a while in theaters and clubs all over Paris, hanging out with Ethel Waters and securing a contract to star in Lew Leslie’s Blackbirds back in New York. While at sea on her way home, the stock market crashes on Oct 24, 1929, kicking off the Great Depression that is to last 10 years. Blackbirds is postponed. Valaida heads back to France to sing, dance and play the trumpet and violin in the show Liza, where one critic describes her as a woman who “whistles like a bird, plays cornet with heart-rending virtuosity and goes all out with tireless jazz that would wake the dead.” She performs in Sweden and Italy before finally returning to New York.

In 1930, Lew Leslie casts Valaida as the star of his new show, Rhapsody in Black, and then, finally, in her own country, Valaida becomes a star.

Valaida is so popular, she is often compared to stage-sensation Josephine Baker, known for dancing in a skirt made of only 16 bananas. Valaida buys a US$25,000 orchid-colored Mercedes and cruises around town with a chauffeur and a pet money both rigged out in matching purple suits and hats.

Valaida is so popular, she is often compared to stage-sensation Josephine Baker, known for dancing in a skirt made of only 16 bananas. Valaida buys a US$25,000 orchid-colored Mercedes and cruises around town with a chauffeur and a pet money both rigged out in matching purple suits and hats.

The life of a jazz musician suited Valaida. She traveled, led orchestras, produced shows and had a full love life.

“She just loved a good time and she had to have the best of everything,” one of her lovers, musician Earl Hines, once said.

When she is 27, she marries teenaged dancer Ananias Berry, who is either 17 or 18 at the time. Valaida had met Nyas in Paris when he was 16 and dancing with his brother at the Moulin Rouge. Nyas’s outraged father wages a war against the couple, including taking Valaida to court on charges of bigamy, of which she is found guilty. Her marriage with the then-19-year-old Nyas is annulled. She must have fixed her situation with her previous marriage, because she and Nyas are remarried three months later. This time it lasts almost three years.

When she is 27, she marries teenaged dancer Ananias Berry, who is either 17 or 18 at the time. Valaida had met Nyas in Paris when he was 16 and dancing with his brother at the Moulin Rouge. Nyas’s outraged father wages a war against the couple, including taking Valaida to court on charges of bigamy, of which she is found guilty. Her marriage with the then-19-year-old Nyas is annulled. She must have fixed her situation with her previous marriage, because she and Nyas are remarried three months later. This time it lasts almost three years.

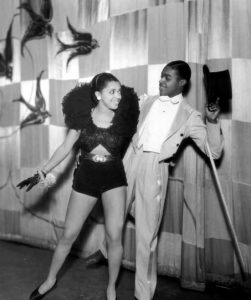

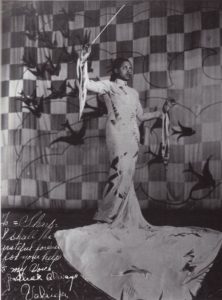

Here are Valaida and Nyas performing together in Blackbirds in London in 1934.

Valaida was just shy of 5 feet tall and had a magnetic and sensual stage presence with expressive eyes and an elegant form-fitting wardrobe. Valaida could be dramatic: she was once late for her ship to Ireland so she got a motorcycle escort with sirens and had to throw herself on board to the cheers of the passengers because the gangplank was already up. Other times, she was the ultimate professional, cool under pressure. Once at the Regal Theater, she played her trumpet so hard and high that she busted her stitches from a recent accident and was bleeding down the back of her head. She just kept smiling and playing.

Valaida returns to tour Europe in the late 30s and is in Denmark when Germany invades in 1940. She continues to perform around Scandinavia, and in 1942, is taken into custody by Danish police for 10 weeks for illegally having the opioid painkiller Oxycodone as well as an unusually large collection of stolen restaurant silverware. They kindly put her on a boat back to New Jersey.

Valaida returns to tour Europe in the late 30s and is in Denmark when Germany invades in 1940. She continues to perform around Scandinavia, and in 1942, is taken into custody by Danish police for 10 weeks for illegally having the opioid painkiller Oxycodone as well as an unusually large collection of stolen restaurant silverware. They kindly put her on a boat back to New Jersey.

Not long after she returns, Valaida begins to tell the story that she had been held in solitary confinement in a Nazi concentration camp for eight months and beaten and starved. She says she was released when the US State Department intervened on her behalf and that all of her money was taken by the Nazis. Later, the story becomes that she was in the camp for two years and lashed with a bull whip every morning. She starts getting lots of gigs.

Nearly everyone says her suffering makes her a better player.

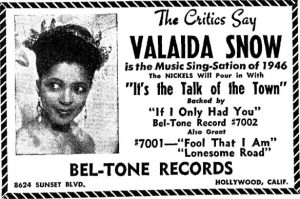

In 1943, she marries for the third time, this time to a comedian named Earle Edwards. In 1945 she signs with LA label Bel-Tone.

Here is a wonderful clip of Valaida playing the trumpet and singing Patience and Fortitude in a short Soundie musical clip from 1946.

Here is a wonderful clip of Valaida playing the trumpet and singing Patience and Fortitude in a short Soundie musical clip from 1946.

And here’s another one of her singing “If you only knew.”

The second photo is of Valaida playing in front of 10,000 people at Wrigley Field with Count Basie in 1945.

Even in the 40s, Valaida is still up to her tricks. Trumpeter Clora Bryant sees Valaida on stage in LA, wearing an off the shoulder white dress with a fitted waist and a full skirt. She strolls out singing “My heart belongs to Daddy,” and then, with a flourish, she pulls out a trumpet hidden in one of her pockets and plays as heartfelt as she can.

Even in the 40s, Valaida is still up to her tricks. Trumpeter Clora Bryant sees Valaida on stage in LA, wearing an off the shoulder white dress with a fitted waist and a full skirt. She strolls out singing “My heart belongs to Daddy,” and then, with a flourish, she pulls out a trumpet hidden in one of her pockets and plays as heartfelt as she can.

Valaida continues to perform and record through the 40s and into the 50s, even playing at Cafe Society in 1951. In 1956, at the age of 51, Valaida dies from a cerebral haemorrhage in New York.

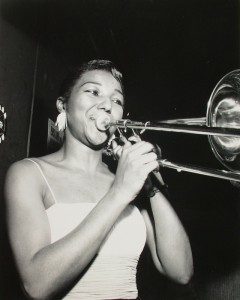

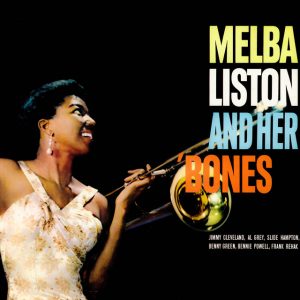

Melba Liston was one of the greatest jazz trombone players of the 40s, 50s and 60s and one of the greatest jazz arrangers that every lived.

Melba Liston was one of the greatest jazz trombone players of the 40s, 50s and 60s and one of the greatest jazz arrangers that every lived.

If Chicago had the Stroll and New York had Lenox Ave in Harlem, then LA had Central Avenue. In 1942, the Avenue is packed with bars and clubs, all clustered around the epicentre of the LA jazz scene, the Dunbar Hotel. Just up the street, 16-year-old Melba Liston from Kansas City is playing and arranging in the house band at the Lincoln Theater, the historical grand music venue sometimes called the “West Coast Apollo.”

Melba is a phenomenal trombone player; she’s been playing since she was 7. She even played on local radio when she was 8. As a member of the band she also starts arranging and composing, which she will do for the rest of her career.

In 1944, Melba starts touring with trumpeter Gerald Wilson’s band, which launches her career as the first woman trombonist to play in the men’s big bands and the first woman to solo on the trombone.

Melba makes one of her first recordings in 1947 with her old school friend Dexter Gordon (right photo) when she joins his band. He wrote the song “Mischievous Lady” just for her, giving her a big trombone solo about halfway in.

Melba makes one of her first recordings in 1947 with her old school friend Dexter Gordon (right photo) when she joins his band. He wrote the song “Mischievous Lady” just for her, giving her a big trombone solo about halfway in.

Not too long after, Melba goes on tour with Count Basie and then Billie Holiday’s band in the South. Melba hates it. Audiences can’t dance to the new bebop style, and Melba is quickly fed up with both the racism and the sexism. So she quits performing for a while.

Not too long after, Melba goes on tour with Count Basie and then Billie Holiday’s band in the South. Melba hates it. Audiences can’t dance to the new bebop style, and Melba is quickly fed up with both the racism and the sexism. So she quits performing for a while.

She comes back in 1958 to make her only album, Melba Liston and her ‘Bones, which is also here only attempt at being a bandleader. She wrote four of the 12 songs.

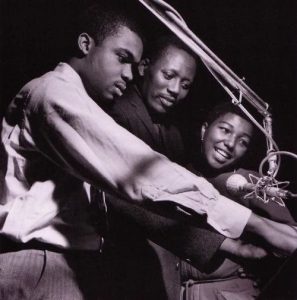

Just after recording the album, she goes on tour with the Quincy Jones (left photo) Orchestra and there are two videos of her playing with them in 1960: “Everybody’s Blues” from their Belgium tour and “My Reverie”, which she arranged, from their Switzerland show. She did a lot of composing for the band.

Just after recording the album, she goes on tour with the Quincy Jones (left photo) Orchestra and there are two videos of her playing with them in 1960: “Everybody’s Blues” from their Belgium tour and “My Reverie”, which she arranged, from their Switzerland show. She did a lot of composing for the band.

In the 1960s, Melba meets pianist Randy Weston (right photo, middle) and the partner up musically for the rest of her life. She mostly arranges for Randy, and start experimenting, mixing African rhythms with traditional jazz, such as in this song Uhuru Kwansa.

She also plays in and arranges for Charlie Mingus in the famous fiasco of a live recording, his Town Hall concert in 1962.

She also plays in and arranges for Charlie Mingus in the famous fiasco of a live recording, his Town Hall concert in 1962.

In 1973, Melba moves to Jamaica for six years and is as the Director of Popular Music Studies at the Jamaica Institute of Music and even works with Bob Marley.

She stopped working after a series of strokes in 1989 and Melba dies in 1999 at the age of 73.

Here is a wonderful video of Melba playing in New York in 1981. And here’s a nice NPR piece on her.

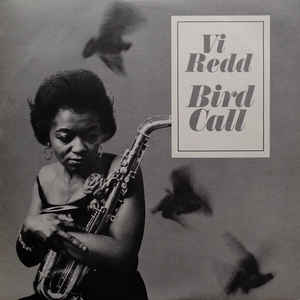

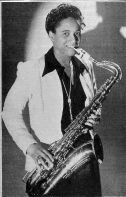

One of the most talented alto sax jazz players and a classmate and good friend of Melba’s, is Elvira Redd, known as “Vi.” In 1940, 12 year old Vi is just starting to learn the alto sax and she will grow up playing the horn in the new bebop style.

Born in Los Angeles to a New Orleans musical family in 1928, Vi has played with all the greats, Count Basie, Max Roach, Sarah Vaughan, Dizzy Gillespie, Dexter Gordon, Marian McPartland and Earl Hines. She was a singer and a bandleader and in the 60s was the first woman to headline an international jazz festival. Vi is still alive and kicking today, in her 90s living in California.

Here is a fabulous video of Vi singing and playing “Stormy Monday Blues” with Count Basie in 1968.

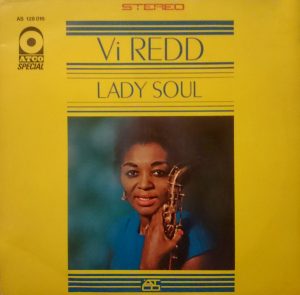

Vi is often compared to bebop legend Charlie Parker, and her first album, recorded in 1962, is named Bird Call in tribute to him. She sings on a number of the songs and has a beautiful raspy voice.

Vi is often compared to bebop legend Charlie Parker, and her first album, recorded in 1962, is named Bird Call in tribute to him. She sings on a number of the songs and has a beautiful raspy voice.

Vi was most active in the 60s, when she performed and toured regularly: in the US and Canada with Earl Hines in 1964; in San Francisco with her husband drummer her husband, drummer Richie Goldberg; with drummer Max Roach; in London in 1966; with Dizzy Gillespie in 1968; with the Count Basie Orchestra in 1968; with Marian McPartland in 1969.

Here’s another video of her singing and playing with Count Basie in 1968. She mostly sang with Count Basie because his lead saxophonist didn’t like it when she played.

But she didn’t record all that often. Her second and last album came out in 1963. The record producers had her sing more than she played. Vi wasn’t happy with the record saying, “it wasn’t the right thing to do.”

But she didn’t record all that often. Her second and last album came out in 1963. The record producers had her sing more than she played. Vi wasn’t happy with the record saying, “it wasn’t the right thing to do.”

Vi received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Los Angeles Jazz Society in 1989, and in 2001, she received the Mary Lou Williams Women in Jazz Award from the Kennedy Center. Here’s a 1-hour long interview about her career with a 71-year-old Vi.

Episode 04

Real Gone Gals

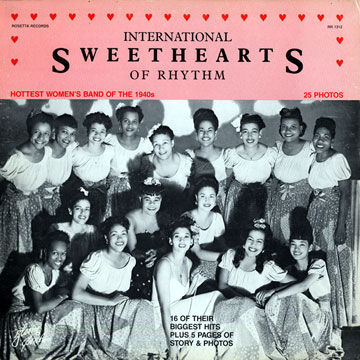

In this episode, I talk to you about the International Sweethearts of Rhythm, one of the hottest swing groups of the 1940s that toured the United States and Europe, playing at some of the most popular theaters of the day, breaking box office records wherever they went, beloved by the public and made up of some of the best jazz musicians in the country.

This is the fourth episode of a series aired on RTHK Radio 3 in Hong Kong in August 2019, written and presented by Robin Ewing and produced by Phil Whelan.

Episode 04 Notes: Photos and Videos of the International Sweethearts of Rhythm - Click the + on right to open notes

The International Sweethearts of Rhythm were one of the hottest swing groups of the 1940s that toured the US and Europe, playing at some of the most popular theaters of the day, breaking box office records wherever they went, beloved by the public and made up of some of the best jazz musicians in the country.

The International Sweethearts of Rhythm were one of the hottest swing groups of the 1940s that toured the US and Europe, playing at some of the most popular theaters of the day, breaking box office records wherever they went, beloved by the public and made up of some of the best jazz musicians in the country.

The Sweethearts were the first racially-integrated band in the United States. They weren’t the first all-female group, there have been hundreds since the 19th century, but they were the most popular, dubbed “America’s No. 1 All-Girl Orchestra.”

The International Sweethearts of Rhythm are one of the most extraordinary stories in the history of jazz.

The Sweethearts of Rhythm started in 1937 in Piney Woods, in the Mississippi Delta, at a Christian boarding school for poor and orphaned black children. The first school band was made up of a group of teenaged girls, many of them orphans who had never even heard jazz before, because of course it was the devil’s music.

The Sweethearts of Rhythm started in 1937 in Piney Woods, in the Mississippi Delta, at a Christian boarding school for poor and orphaned black children. The first school band was made up of a group of teenaged girls, many of them orphans who had never even heard jazz before, because of course it was the devil’s music.

15-year-old Chinese-American Willie Mae Wong was recruited to play the baritone sax so that the school could add the word “international” to their name. They also had Alma Cortez, a Mexican clarinettist; Nina de La Cruz, a Native American saxophonist, and Nova Lee McGee, a native Hawaiian trumpet player.

The band started played local community centers and churches and by 1939 they were good enough to take the show on the road, using an old school bus converted into a tour bus with a study area, dressing rooms and bunk beds. They call it Big Bertha. The Sweethearts begin to tour the country, wowing audiences and winning contests.

By 1941, the group of teenage orphans, now young women, were fed up with the school’s mismanagement of the band; they were making next to nothing while the school took all the money. The girls, along with their school-appointed chaperone Rae Lee Jones, steal Big Bertha and run away with all the instruments. In response, the school has the police out looking for the runaways to arrest them for theft. The girls abandon the bus in Alabama and make a break for Washington DC where they finally break free of the school. They find a sponsor and hire a musical director. The girls go pro.

By 1941, the group of teenage orphans, now young women, were fed up with the school’s mismanagement of the band; they were making next to nothing while the school took all the money. The girls, along with their school-appointed chaperone Rae Lee Jones, steal Big Bertha and run away with all the instruments. In response, the school has the police out looking for the runaways to arrest them for theft. The girls abandon the bus in Alabama and make a break for Washington DC where they finally break free of the school. They find a sponsor and hire a musical director. The girls go pro.

The new musical director, Eddie Durham (who had worked with Ina Ray Hutton, Benny Moten, Count Basie, Jimmie Lunceford, Artie Shaw and Glenn Miller) whips the girls into shape and books them at the Howard Theater in Washington DC. There they sell 35,000 tickets and break box office records.

Next up is the Apollo Theatre, the country’s most demanding stage. This is the moment they have been preparing years for. The Apollo makes or breaks bands.

In this photo we can see the saxophone choir at the Apollo in 1942. From top left moving clockwise: Marge Pettiford, Helen Saine, Amy Garrison, Wille Mae Wong, Grace Bayron.

The Sweethearts play for the toughest audience in show businesses, and the crowd goes wild, dancing in the aisles, cheering, stamping and clapping as the 17 women swing the house. The show is a huge success and has Harlem talking for weeks. Next month the Sweethearts will go on to enthral the jitterbug dancers at the popular Savoy Ballroom down the street and from here their performing career takes off.

The Sweethearts play for the toughest audience in show businesses, and the crowd goes wild, dancing in the aisles, cheering, stamping and clapping as the 17 women swing the house. The show is a huge success and has Harlem talking for weeks. Next month the Sweethearts will go on to enthral the jitterbug dancers at the popular Savoy Ballroom down the street and from here their performing career takes off.

The photo on the left is the trombone section at the Apollo in 1942: left, Ina Balle Byrd; top Judy Bayron; bottom Helen Jones, the Sweethearts’ original bandleader and adopted daughter of the founder, Dr Laurence C Jones.

The top photo is from when the girl ran to Washington DC with their chaperone, pictured in the top row, third from left.

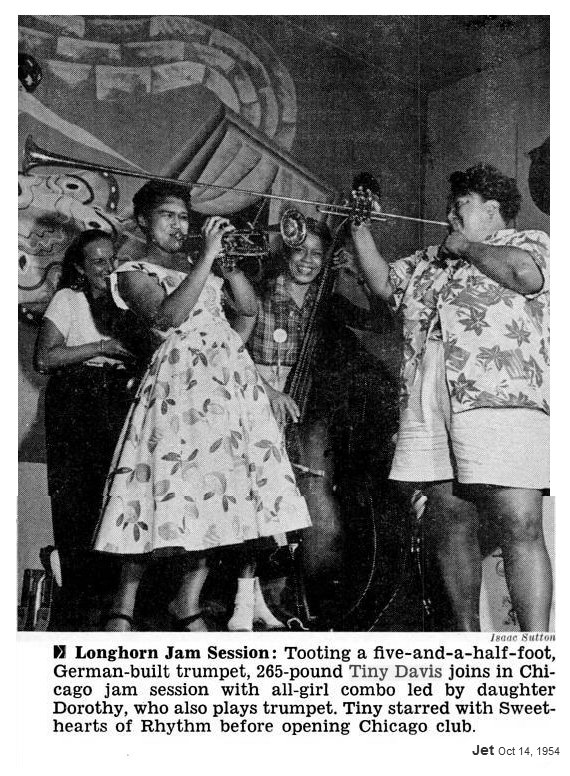

As the band’ s popularity soars, more experienced musicians start joining the group, women like Tiny Davis.

As the band’ s popularity soars, more experienced musicians start joining the group, women like Tiny Davis.

From Memphis, Tennessee, Tiny was billed as “the hottest female trumpeter in the universe” for over 30 years as she played in number of all-women bands. She even turned down a better-paying job with Louis Armstrong to stay with the gals.

Here is a fantastic video of the Sweethearts with Tiny Davis singing, dancing and playing trumpet. Her trumpet solo is short, but you can really hear her power and her talent. This soundie takes from one of their regular numbers, “Jump Children.”

Jezebel Productions made a documentary about the Sweethearts and about Tiny Davis. You can see a 7-min clip about Tiny from the film here.

Tiny eventually left to form her own band, Tiny Davis and her Hell Divers, with her long-term partner Ruby Lucas who played bass and drums. They recorded a number of single on Decca records, but they are hard to find. Here’s a recording on one of her popular songs, “Race Horse,” released in 1950.

Tiny eventually left to form her own band, Tiny Davis and her Hell Divers, with her long-term partner Ruby Lucas who played bass and drums. They recorded a number of single on Decca records, but they are hard to find. Here’s a recording on one of her popular songs, “Race Horse,” released in 1950.

In the 50s, the couple opened a very popular club called “Tiny and Ruby’s Gay Spot” in South Chicago where they continued to perform. Tiny’s teenaged daughter Dorothy often played trumpet, keyboards and bass with the band. Tiny sold the club and started touring again in 1955.

Tiny lived well into her 80s, dying in Chicago in 1994.

Another Sweethearts superstar was Violet Mae “Vi” Burnside who played lead tenor sax. From Lancaster, PA, Vi played in all-women bands, such as the Dixie Rhythm Girls and the Harlem Playgirls, with Tiny before joining the Sweethearts in 1941.

Another Sweethearts superstar was Violet Mae “Vi” Burnside who played lead tenor sax. From Lancaster, PA, Vi played in all-women bands, such as the Dixie Rhythm Girls and the Harlem Playgirls, with Tiny before joining the Sweethearts in 1941.

She later formed her own band, touring the US, and she packed the clubs. She was known to jam with Ben Webster and she was famous for winning cutting contests with other saxophonists.

Saxophonist Willene Barton once said, “After the Sweethearts broke up, every manager, everybody in New York, was after Vi Burnside, so she easily got herself a group and traveled all over. I have never seen a woman command that much attention as far as a horn is concerned. I mean, she showed up in every big city in America. She made her debut at a club called the Baby Grand in Harlem, and I understand that you couldn’t get near the door. It was like that at every club she went to with her band. Well, this particular time she was in Cleveland, and she was QUEEN of the show, of course. In those days everybody came to see what the tenor player was made of.”

In the photo, Vi is on the far left in the tuxedo. Tiny is second from right also in a tuxedo.

In the photo, Vi is on the far left in the tuxedo. Tiny is second from right also in a tuxedo.

Vi died young at the age of 49 in 1964 and though there are rumors that she recorded a record with Abbey records, it has never been found.

Here is a video of the International Sweethearts of Rhythm playing “She’s Crazy with the Heat.” Vi has a stand out sax solo at 1 minute.

Saxophonist Roz Cron was one of the few white woman in the band. When the women played in the South, under strict Jim Crow laws that did not allow mixed-race groups to play together, police would show up to intimidate the crowd and make sure there were no white women in the band. Roz would perm her hair and wear dark makeup on stage. On one particularly frightening evening in South Carolina, the band, while in full swing on stage, artful positioned themselves to shield Roz from the gaze of two sheriffs . In 1944 she was arrested in El Paso, Texas for attempting to “pass for black” but was released when a black bandmate showed up at the jail and told police she was Roz’s cousin.

Saxophonist Roz Cron was one of the few white woman in the band. When the women played in the South, under strict Jim Crow laws that did not allow mixed-race groups to play together, police would show up to intimidate the crowd and make sure there were no white women in the band. Roz would perm her hair and wear dark makeup on stage. On one particularly frightening evening in South Carolina, the band, while in full swing on stage, artful positioned themselves to shield Roz from the gaze of two sheriffs . In 1944 she was arrested in El Paso, Texas for attempting to “pass for black” but was released when a black bandmate showed up at the jail and told police she was Roz’s cousin.

The Sweethearts really fought two fronts, prejudice against both race and gender. After that Apollo debut, a group of male musicians got together to demand the owner of the Apollo let them backstage so they could see what male band was really playing as it was obvious the women were pantomiming. “Ain’t no girls can play like that,” one said. Imagine their shock when they discovered it wasn’t a trick.

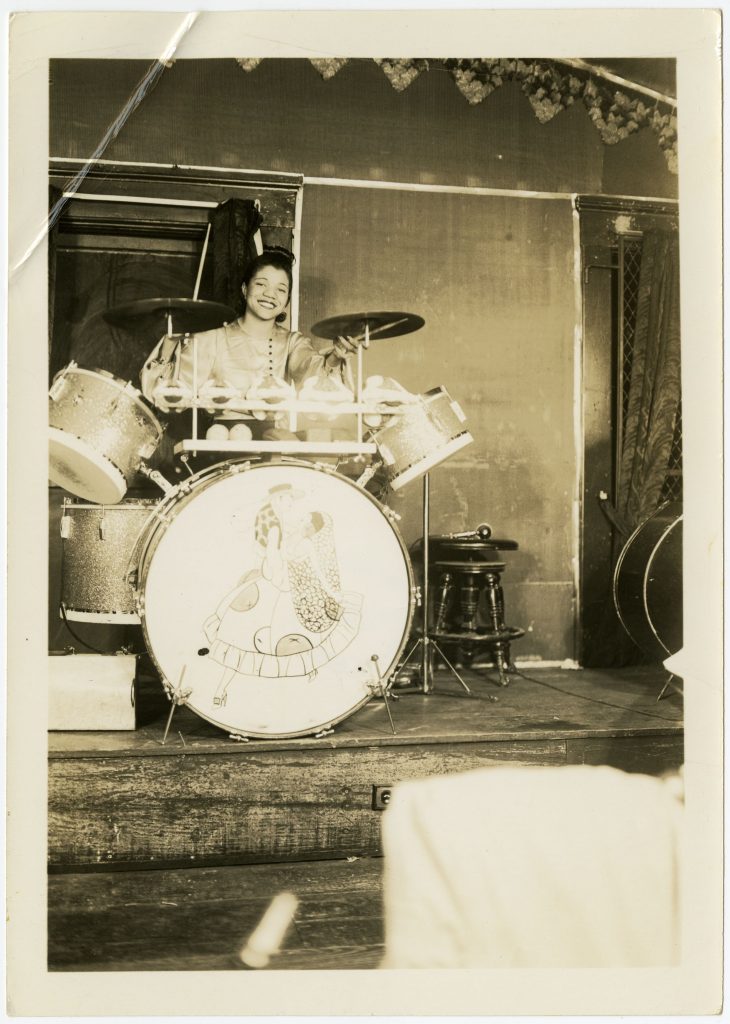

While many of the more famous players, like Tiny, Vi and Roz, joined later in the sweethearts career, drummer Pauline Braddy was an original member and one of the most important sweethearts known all over the US as the “Queen of the Drums.”

While many of the more famous players, like Tiny, Vi and Roz, joined later in the sweethearts career, drummer Pauline Braddy was an original member and one of the most important sweethearts known all over the US as the “Queen of the Drums.”

Pauline powered the band. Showstopping songs were written just for her to showcase her superb drumming skills. In one of these songs, she performed in the dark and under a blacklight wearing white gloves with her sticks, cymbals and rims covered in fluorescent paint.

“This young swing drummer is one of the reasons why the International Sweethearts of Rhythm is by far the most popular girls’ orchestra in the country today,” one Chicago newspaper said.

Pauline left the Sweethearts when she was 33 and played in various jazz ensembles all over the US, including with Vi Burnside, until the 1960s when she settled in Washington to take care of her mother. She was a switchboard operator there for 20 years.

Pauline died in Mississippi in 1996 at the age of 73.

Another originial Sweetheart was saxophonist Wille Mae Wong, whose real last name was Lee. Willie Mae’s father was Chinese and the school recruited her when she was 15 to play the baritone sax so they could add the word “international” to the name. She was playing stickball in the street when they found her. Her nickname became “Rabbit” because the music director had to spend time with her to teach her the beat. She had never heard music before.

Another originial Sweetheart was saxophonist Wille Mae Wong, whose real last name was Lee. Willie Mae’s father was Chinese and the school recruited her when she was 15 to play the baritone sax so they could add the word “international” to the name. She was playing stickball in the street when they found her. Her nickname became “Rabbit” because the music director had to spend time with her to teach her the beat. She had never heard music before.

Willie Mae died in 2016 at the age of 96.

There were so many incredible musicians in the Sweethearts that came and went over the years it would be impossible to tell you about all of them. But, for the final years, there was one constant, Anna Mae Winburn.

There were so many incredible musicians in the Sweethearts that came and went over the years it would be impossible to tell you about all of them. But, for the final years, there was one constant, Anna Mae Winburn.

Anna Mae was hired to be the new band leader just after the girls went pro. Her nickname was the “Bronze Venus ” and she was glamorous, experienced and had a fantastic sense of rhythm. Under Anna Mae, the women start wearing uniforms, a white blouse, black skirt and red jacket, adding to their professionalism. Anna Mae could play piano and guitar, but for the sweethearts, she always stood in front, in a long stylish gown, and kept the band on point.

Here’s a great video of Anna Mae singing with the Sweethearts with “Jump Children.” Vi’s got a nice solo at 1:35 too.

In 1945, the Sweethearts flew to Europe on a USO tour to play for the American soldiers. They were a hit and the women came home with more money then they had ever had.

In 1945, the Sweethearts flew to Europe on a USO tour to play for the American soldiers. They were a hit and the women came home with more money then they had ever had.

In the first photo, from left to right, are Wille Mae Wong, Anna Winburn and Vi Burnside.

In the second are Tiny and Willie Mae.

The end of the Sweethearts was pretty much the end of the all-women swing big bands of the 1940s. In the decades that followed, a whole new group of women musicians made, played an changed jazz. Mary Osborne set the bar for jazz guitar. Pianist Nina Simone wrote and sang songs that became anthems for the Civil Rights movement. Alice Coltrane and Dorthy Ashby transformed the sound of the jazz harp. Marian McParland and Mary Lou Williams became two of the greatest pianists in jazz history. And then there are the vocalists: Sarah, Ella, Dinah, Billie. But that is for another show.

The end of the Sweethearts was pretty much the end of the all-women swing big bands of the 1940s. In the decades that followed, a whole new group of women musicians made, played an changed jazz. Mary Osborne set the bar for jazz guitar. Pianist Nina Simone wrote and sang songs that became anthems for the Civil Rights movement. Alice Coltrane and Dorthy Ashby transformed the sound of the jazz harp. Marian McParland and Mary Lou Williams became two of the greatest pianists in jazz history. And then there are the vocalists: Sarah, Ella, Dinah, Billie. But that is for another show.

Here is another video from one of the greatest jazz swing bands in history: The International Sweethearts of Rhythm playing “I Left my Man” with Anna Mae singing, and Tiny on trumpet along with fellow trumpeter Johnnie Mae Stansbury.

Here is a Smithsonian video of a group of some of the Sweethearts getting together for a discussion in 2011. The women, who are in their 80s in the video, include trombonist Lillie Keeler Sims; saxophonist Rosalind Cron; trumpter Sadye Pankey Moore; trombonist Helen Jones Woods